Guildhall. City of London: Part 2

The Great Hall – from Medieval to Victorian London.

Continuing our exploration of Guildhall, this post looks at the architectural history, up to the 20th century, of its original and most important building. For centuries the words ‘Guildhall’ and ‘the Great Hall’ were interchangeable. Today the Guildhall complex is made up of lots of buildings but the Great Hall is still at its epicentre.

For an explantion of what Guildhall is and its purposes have a look at the posting: Guildhall. City of London: Part 1.

Medieval London

Although Guildhall’s origins are obscure, we do know that the present Great Hall is not the first to be constructed on the Guildhall site. When the first one appeared we are not sure, possibly during the late Anglo-Saxon period. There is archaeological evidence that an earlier Great Hall existed by the late thirteenth century and the name ‘Guildhall Yard’ was commonly used from the late thirteenth century. The west crypt in the undercroft of the Great Hall is now known to have been a part of an earlier Guildhall building.

Nor is much is known about John Croxtone, builder and designer of the Great Hall, although we can assume that he was a master mason and had perhaps been involved in church building. The architecture of the Great Hall is cathedral-like and borrows much in style and execution from church construction of the time; it even faces west to east.

The Great Hall: 15th century (Mark Carter)

Started in 1411 and completed by 1429 it was, and still is, the second largest single span great hall in Britain. Only Westminster Hall at Parliament is larger. Although we know little of Croxtone we do know that he worked under the master mason Henry Yevele, during his rebuilding work at Westminster Hall.

Croxtone followed the English Perpendicular style, which dominated the later Gothic styles of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The Great Hall was the largest building in the City of London, apart from St Paul’s Cathedral. An ornate Gothic style porch served as entrance and ante-chamber to the Great Hall.

Croxtone’s roof for the Great Hall has always been something of a mystery. It seems Croxtone prepared for stone arches but that budget constraints probably resulted in a pitched timber roof.

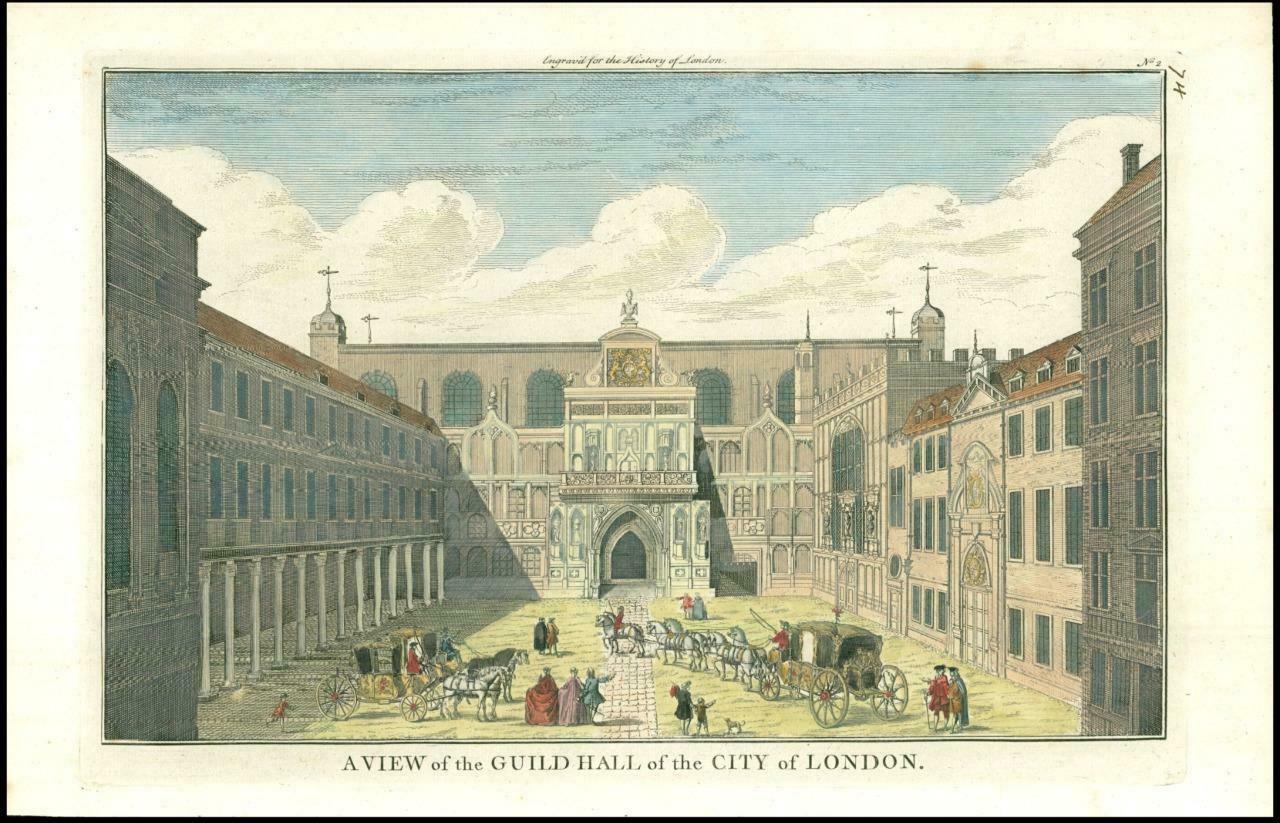

The exterior was not smoothly finished or decorated to an exceptional level. There was no need. It’s worth remembering that Guildhall was built in a crowded city with narrow streets and lanes on all sides. Guildhall Yard was barely wider than the porch itself. The full length of the Great Hall would have been obscured until you were actually standing within its vast interior. This narrow approach through the Yard was the terrain that would have greeted the visitor until after the Second World War.

By its completion the Guildhall consisted of the Great Hall, plus the Mayor’s Court and Court of Aldermen on the north side, with the porch to the south and the crypts in the undercroft. To reflect its burgeoning use as a venue for banqueting and ‘gaudy days’ a kitchen, buttery, pantry, ovens, larder and wine and ale cellars were added in the sixteenth century.

A boundary wall to Guildhall Yard’s west side and a gatehouse on the southern boundary had already existed, it’s thought by the late thirteenth century. The entire Guildhall site was now surrounded by a wall with a rebuilt gatehouse, to create a precinct around all of the surrounding buildings. Again, this borrowed from the construction of English cathedral’s, which were all enclosed within a close.

Why was there this big push to build a complex of grand secular buildings in late middle ages London? Money may provide part of the answer. We can assume that the wealth now existed within the City to fund large parts of this ‘status symbol’ project. Influence may also have mattered, with wealthy merchants now able to support and be seen supporting such a prestigious project – although various taxes also funded its building.

Another reason may have been to emphasise the point that London was not just a trading city, but a mercantile centre capable of competing with the other great trading cities of continental Europe. Size mattered and the Great Hall was built on a scale to impress. At its centre presided its secular emperor, a man neither royal nor religious, but a trader: the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

The Great Fire of London: 1666

The areas of London affected by the Great Fire went beyond Guildhall. Most of the Great Hall’s roof was destroyed, but the interior of the Great Hall itself survived.

Great Hall and Guildhall Yard: mid 18th century

A new roof, intended as a temporary replacement, lasted for 200 years. This replacement was a flat timber roof, covered by a shallow layer of pitch. It was also higher than the old roof by between ten to twenty feet, with a clerestory (upper windows) adding more light. The new interior ‘ceiling’ was probably panelled in order to provide decoration and an illusion of depth.

Christopher Wren may have provided some oversight although his involvement is unclear and somewhat disputed. It seems more likely that Peter Mills, City Surveyor until 1671, oversaw and designed most aspects of the earlier repairs. A baroque style gable was also added to the top of the Gothic porch at his time, it would seem by either Mills or Wren.

The most significant legacy of Wren’s involvement has nothing to do with the fabric of Guildhall. It is in fact Wren’s planning of the long wide street that leads from the River Thames north towards Guildhall. It seems such a natural approach today, but King Street and Queen Street did not exist at all until after the Great Fire. Ironmonger Lane and Lawrence Lane, being two narrow streets that we would nowadays consider no wider than alleys, had been the main approaches since the early middle ages.

With the idea of greater visibility in mind Wren also demolished the outer precinct wall and gates, or what little had survived the Great Fire. Instead of looking for inspiration towards the English cathedral enclosure, Wren was now looking to Paris and Versailles, imitating the Continental fashion for openness and accessibility.

Ogilby & Morgan Map 1677 (detail)

Victorian Renovation

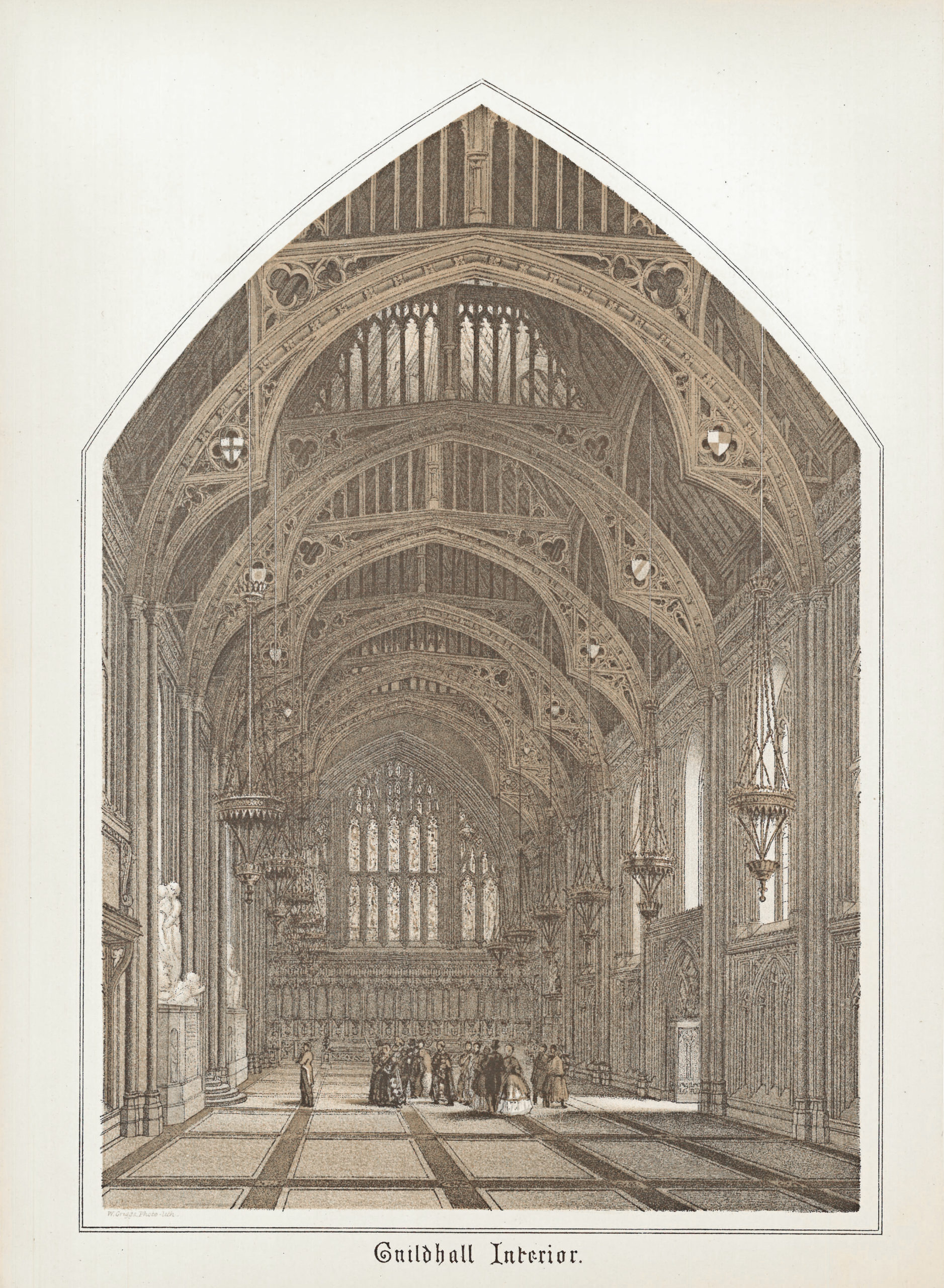

Sir Horace Jones’s Great Hall renovation with hammer-beam timber roof.

Full renovation of the Great Hall, and rebuilding and expansion, would not occur until the 1860s. Sir Horace Jones, Surveyor to the City, began to carry out extensive works. By the mid-nineteenth century Gothic revivalism had become the fashionable architectural style of choice for many public works, private buildings and new churches.

Following its destruction by fire in 1834 the Houses of Parliament had been almost completely rebuilt in the Gothic style.

Sir Horace Jones by contrast had an original and almost complete Gothic building to work with. Where original Gothic features had been replaced with Baroque or neo-Classical renovation and repair, Jones re-Gothicised; and like Croxtone four centuries earlier, Jones was inspired by the splendour of Westminster Hall – which had been saved from the fire at Parliament.

The most significant part of Jones’s renovation was the construction of a Westminster Hall style hammer-beam roof, the like of which Croxtone hadn’t actually constructed. The carving, guilding and painting were redone and, most significantly, reinterpreted to create a Great Hall as it may have looked during its Plantagenet and Tudor heyday.

Unfortunately for Jones it was always the opinion that his faux-medieval timber roof was a failure; too heavy and squat, darkening what could have been a lighter space (remember, this was the man who also designed Tower Bridge and Leadenhall Market).

Guildhall Porch

The old Croxtone porch resembled a large elaborate church porch. It faced onto Guildhall Yard and could be easily be seen, whilst the rest of the walls were partly obscured by other buildings. The new porch was designed by George Dance the Younger, Surveyor to the City almost a century before Sir Horace Jones, and it is huge.

Croxtone’s porch was intended to be a symbolic entrance for a building looking forward to a London sharing parity with Europe’s great trading centres. Dance’s porch was to be a symbolic entrance for a building looking forward to British imperial power.

The Great Hall today with Dance’s ‘Hindoo Gothic’ porch

Dance’s porch is built as high as the Great Hall and it was completed in 1789. Its style, relatively unique, is described as ‘Hindoo Gothic’, although it integrates elements of Croxtone’s Gothic with the neo-classical fashions of Dance’s time. In fact the interior of Croxtone’s porch can still be seen when entering the Great Hall through the porch. His low, vaulted ceiling is enveloped by Dance’s radical new building.

The question concerning the porch has tended to be, why ‘Hindoo Gothic’? There may be many reasons. Dance was an experimental and creative designer at the same time that the inclusion of India into the Empire was progressing apace. Eastern influences were beginning to spread, including within the arts. Dance’s friend, the artist William Hodges, had recently returned from India and some of his paintings of Indian landscapes, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1786, would surely have been seen by Dance.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy, said of Hodges’s exhibition ‘The Barbaric Splendour of those Asiatic Buildings, which are now publishing by a member of this Academy may possibly…furnish an architect…with hints of composition and general effect that would not otherwise have occurred.’

The Indian details, which can be seen most visibly in the windows and the outline of the turrets, are clearly a nod to the eastern influences newly imported from the far reaches of Empire. It’s entirely possible to interpret Dance’s porch as a statement of the new reality too; a patriotic gesture and affirmation of Britain’s expanding imperial interests.