Queen Victoria Memorial versus The Albert Memorial: Part 1 – Albert

The Albert Memorial (real name: Prince Consort National Memorial)

Kensington Gardens, London SW7.

This is the first part of my definitive guide to the Queen Victoria Memorial and to the Albert Memorial. Married in life, separated by death and each the recipient of a grand, excessive and elaborately detailed London memorial. Victoria and Albert were a pair in life and are now combatants in a face-off to see who has the most overblown and extravagant memorial in London. Why ‘Albert’ first? He died first and this memorial is older.

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (August 1819-December 1861) was the German husband and cousin of Queen Victoria. When he died suddenly of typhoid fever the Queen went into permanent mourning and became such a recluse she was soon referred to as ‘the widow of Windsor’.

Albert Memorial

Albert was a cultured man and at first felt constrained by his role as consort to Victoria. He began to take an interest in public causes and became dedicated to social progress, reaching the peak of his influence when he served as President of the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Great Exhibition (full name ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’) ran from May – October 1851 and could be considered the world’s first great expo. Over six million people visited including, on several occasions, Victoria and Albert themselves. The Great Exhibition took place within the specially built Crystal Palace, in Hyde Park, a short distance from where the Albert Memorial stands.

When Albert died a memorial was considered almost immediately. A committee was formed and ideas came and went, including a giant red granite obelisk and statuary with Albert on a horse. Eventually Gilbert Scott and his Gothic ‘everything-but-the-kitchen-sink’ design was selected. The memorial was paid for by public subscription, Queen Victoria and Parliamentary grants (Gladstone against, Disraeli for).

The Albert Memorial is also, arguably, a bombastic tribute to Great Britain’s powerful Empire and its muscular Christianity. It portrays a very Anglo-centric worldview and was made with the best of intentions and without a shred of self-awareness. Don’t get me wrong. I love this crazy memorial. It’s unique, a feast for the eyes and – mostly – great fun.

Architect: Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

Dates: Commissioned April 1863. Opened 3rd July 1872. Completed 1876.

Materials: Scottish and Cornish granite, Derbyshire sandstone, slate, glass, marble, bronze and gilt bronze and gold.

Dimensions: 176 feet/50 metres high.

Architecture: Designed in the Gothic Revival style it takes the form of an ornate free standing canopy in the style of a Gothic ciborium, more usually found over the high altar of a church, sheltering a statue of Prince Albert facing south. Sculptures and allegorical statues decorate the memorial from ground level to pinnacle.

The Perimeter

Perimeter Railings

The entire memorial is enclosed at ground level within Gilbert Scott’s iron railings, painted mauve and gold, with a floral design worked into fine tracery by Francis Skidmore of Coventry (Skidmore also painted and enamelled the various heraldic shields). This perimeter forms a perfect square around the granite steps which lead up to the ciborium. Breaking the railings, in each corner, stand giant sculptures. Each sculpture represents a continent whose goods were shown at the Great Exhibition:

Europe (SW corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by Europa riding a bull (Europa was the mother of King Minos of Crete from where the Minotaur originates). Four queens in turn represent Britain holding a trident for sea power, France holding a sword, Germany deep in contemplation holding a book and Italy, one hand raised in thought and the other holding a lyre, is focussing on creativity with an artist’s palette resting at her feet. Sculptor: Patrick MacDowell.

Asia (SE corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by a topless Indian woman exotically posed and seated on a kneeling Indian elephant. On her right is a cross-legged Chinese potter and a standing Indian warrior. To her left stands a Persian poet and a reclining Arab merchant. Sculptor: John Henry Foley.

Europe

Europe

Europe

Asia

Asia

Asia

Africa (NE corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by an Egyptian queen sitting on a camel. She wears the Vulture crown, a symbol of protection. Her male servant places his left hand on what appears to be the front elevation of the Sphinx. To the queens left sits an Egyptian merchant. Behind the camel a woman symbolising ‘European Civilisation’ is motioning to a semi naked African who represents emancipation. Prince Albert had been President of the Society for the Extinction of Slavery. Sculptor: William Theed.

America (NW corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by a native American female sitting on a charging bison. She is accompanied by two female standing figures. Pointing to who-knows-where is the United States and more modestly is Canada who holds an English rose to her breast. An Aztec warrior is sitting to the bison’s right and on the left is what looks like a semi-naked North American pioneer with his rifle, but who is supposed to represent South America. Sculptor: John Bell.

Africa

Africa

Africa

America

America

America

The ‘Continents’ are all pyramidal designs and intended to be seen from all sides. The sculptor Henry Armstead coordinated the designs and commissions for all statuary on the memorial.

It would be fair to say that many figures in ‘the Continents’ are represented in a way that we would find unacceptable should they be proposed today. They sometimes blunder thoughtlessly into, what we would recognise as, racist or patronising stereotypes. I’m sure no ill will was intended, it’s just that we view the memorial through very different eyes.

The Frieze of Parnassus

The base (or podium) of the memorial is surrounded by the sculptural ‘Frieze of Parnassus’ (Mount Parnassus was the favourite resting place for the Greek muses). It’s creation and centrality was intended to reflect Prince Albert’s own love of the arts and sciences. The frieze is life size and depicts 169 individuals: composers, poets, painters, architects and sculptors. It measures 210 feet/64 metres.

Great Composers (S side, 1876 – marble) – displayed by national school. Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Great Poets (S side, 1876 – marble) – displayed by national school. Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Great Painters (E side, 1876 – marble) – displayed by national school. Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Great Architects (N side, 1876 – marble) – displayed in chronological order. Sculptor: John Birnie Philip

Great Sculptors (W side, 1876 – marble) – displayed in chronological order. Sculptor: John Birnie Philip

Only one living figure was present; George Gilbert Scott’s head is discretely carved above Augustus Pugin. Each name is carved below their figure. Authentic clothing, accessories and facial hair was portrayed as accurately as possible and many of the figures are in conversation, communicating across time.

Inclusion (and exclusion) mirrored Victorian tastes of the time and there are some questionable inclusions and surprising omissions. This was also the perfect opportunity to place great Britons within the firmament of the universal and classical greats. All of the figures are male.

The Frieze of Parnassus: South

The Frieze of Parnassus: East

The Frieze of Parnassus: North

The Frieze of Parnassus: West

The Useful Arts

Above the frieze, positioned on the external corners of the ciborium are four allegorical sculptures depicting Victorian industrial arts and sciences:

Agriculture (SW corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by a shepherd and his sheep, a woman holding a sheaf of corn and a muscular labourer working modern machinery. He appears to be blessed by the central female figure. It’s all very dignified and romantic. Sculptor: William Calder Marshall.

Manufacturers (SE corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by a working smith, a fabric maker and a potter. The central female figure holds an hourglass. Sculptor: Henry Weekes.

Commerce (NE corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by three merchants and their goods. The central female figure is holding a cornucopia (or horn of plenty). Sculptor: Thomas Thorneycroft.

Engineering (NW corner, 1876 – marble) – is represented by three male figures in both classical and contemporary dress using technical equipment. The central female figure appears curious. Sculptor: John Lawlor.

The Useful Arts and The Intellectual Disciplines: South West

The Useful Arts and The Intellectual Disciplines: South East

The Useful Arts and The Intellectual Disciplines: North East

The Useful Arts and The Intellectual Disciplines: North West

The Intellectual Disciplines (aka the Practical Arts and Sciences)

Above the Useful Arts are eight more allegorical statues in bronze representing the Intellectual Disciplines. The lower four statues each stand on a granite plinth against the polished Ross of Mull granite columns of the ciborium. The four upper statues (level with the mosaic spandrels) stand on stone plinths and within niches, also against the polished Ross of Mull granite columns:

Geometry (SW column lower, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: John Birnie Philip

Astronomy (SE column lower, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Chemistry (NE column lower, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Geology (NW column lower, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: John Birnie Philip

Physiology (SW column upper, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: John Birlie Philip

Rhetoric (SE column upper, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Medicine (NE column upper, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: Henry Armstead

Philosophy (NW column upper, 1876 – bronze) – Sculptor: John Birlie Philip

Prince Albert

The original choice of sculptor – and Queen Victoria favourite – Carlo Marochetti had not impressed with his design and model of Albert. He also died at the end of 1867. In May 1868 John Henry Foley was commissioned to make a portrait and a sketch model, which met with approval. A full-sized model was placed on the monument in 1870 and approved by Queen Victoria. The final statue was cast in bronze by Henry Prince and Company of Southwark. Foley died in August 1874 before casting was complete; his main assistant during his final illness being Thomas Brock who later made the Queen Victoria Memorial.

The gilt bronze statue was ceremonially ‘seated’ in 1875, three years after the memorial opened. Albert is physically seated and shown looking south, towards the Royal Albert Hall. He is robed as a Knight of the Garter and holds a catalogue of the Great Exhibition in his right hand.

Above Albert the interior of the vaulted canopy is painted sky blue with golden stars and heraldic shields in each quarter. A large Tudor rose boss is strengthened by wrought iron to support the weight of the memorial above.

Albert Memorial

Albert Memorial: The Canopy

The Canopy

The columns are of polished Scottish granite. Gilbert Scott chose ‘the best carver I have ever met’, William Brindley, to carry out the architectural stonecarving. Brindley also carved the cornices of the canopy ‘with noble foliage in high and bold relief’ and the gargoyles (which project outwards and drain out the rainwater). Gilding and semi-precious stone completes the Gothic arches.

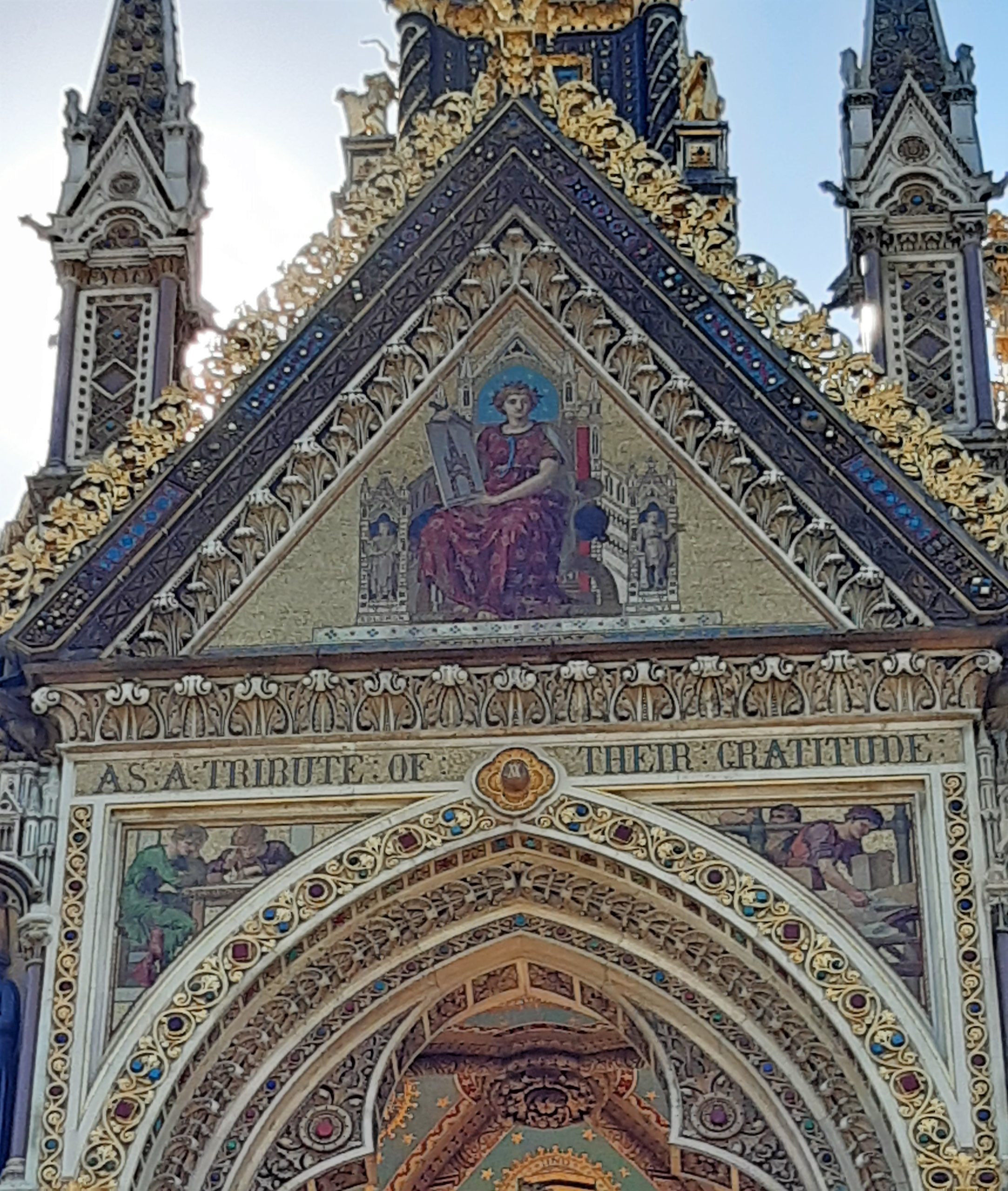

Tympana and Spandrel Mosaics

The canopy tympana features decorative mosaic artworks, designed by John Clayton of Clayton & Bell. The glass was manufactured by A. Salviati of Venice.

Each of the four tympana mosaics displays a central allegorical figure representing the Four Arts supported by two historical figures:

Poesis – Poetry (South): supported by King David and Homer. Poesis holds a scroll which lists Shakespeare, Molière, Milton, Goethe and Homer (again).

Pictura – Painting (East): supported by Apelles and Raphael.

Architectura – Architecture (North): supported by King Solomon and Ictinus. Architecture holds a design of the Albert Memorial.

Sculptura – Sculpture (West): supported by Phidias and Michelangelo.

Below the canopy cornicing is a dedicatory legend in mosaic split into four parts:

QUEEN VICTORIA AND HER PEOPLE . TO THE MEMORY OF ALBERT PRINCE CONSORT .

AS A TRIBUTE OF THEIR GRATITUDE . FOR A LIFE DEVOTED TO THE PUBLIC GOOD

The spandrels portray idealised mosaic figures of Art Workers.

Poesis: South

Pictura: East

Architectura: North

Sculptura: West

The Central Spire

Four gilded heraldic lions sit at the base of the central spire. Just above them are gilded statues of the eight virtues:

Faith, Hope, Charity, Humility, Fortitude, Prudence, Justice and Temperance.

The Virtues are displayed around a miniature version of the main canopy.

Standing on top of this miniaturised ciborium are eight gilded angels tapering upwards. The four angels on the lower row are in mourning. The four angels above are in exultation. Their outstretched arms reach upwards to the golden cross set on top of an orb. This is the pinnacle; we started our journey on earth and are now 176 feet closer to heaven.

The Albert Memorial: The Eight Virtues, Angels and Cross

The Albert Memorial: The Eight Virtues, Angels and Cross

The Albert Memorial: The Eight Virtues, Angels and Cross

Memorial Minutae

-

Beneath the Albert Memorial a ‘vast honeycomb’ of 868 brick arches was built on a foundation of concrete 17 feet thick, to support the granite steps. Described by George Gilbert Scott as ‘a curiously intricate and picturesque series of catacombs’ it is not open to the public, unfortunately.

-

The total cost of the Memorial was very roughly £150,000. The marble statuary alone cost roughly £52,000. There was a surplus of 6,083 16s. 4d. from the money raised. Of that sum over £5,500 was paid to Queen Victoria, with the intention that it should reduce her personal liability for the expenditure on the Prince’s statue.

-

Woolwich Arsenal supplied 71 tons of old bronze guns to be melted down for use in the Memorial, at a cost of £4970.

-

Queen Victoria called the Memorial ‘really magnificent’ and in relation to her usual reclusiveness she had maintained an interest. She was consulted through the entire process and made occasional visits during its construction. In 1866 she wrote ‘All the time I felt a longing to tell my dearest Albert all about it and to hear his words and remarks!’

-

George Gilbert Scott received his knighthood following the unveiling of the Memorial.

-

There is a central axis between the Albert Memorial, through the middle of the Royal Albert Hall, stretching to the central portal of the south façade of the Natural History Museum on Cromwell Road.

-

The writer Osbert Sitwell described it thus: ‘That wistful unique monument to widowhood…that gilded and pensive giant on his dais under the Gothic canopy, strewn with white mosaic daisies of a blameless life.’

-

Almost one hundred years after its completion Ian Nairn decided it looked ‘rich, competent…and completely cold.’

-

The unofficial name ‘Albertopolis’ was given to the area between Exhibition Road and Queen’s Gate, and which stretches south from Kensington Gore to the Cromwell Road. Albertopolis includes: the Royal Albert Hall, Royal Geographic Society, Imperial College, Royal College of Art, Royal College of Music, Victoria & Albert Museum, Science Museum and the Natural History Museum.

-

Albert was painted black, and the rest of the Memorial’s gilding removed, during the First World War so that the floodlights of German Zeppelin airships wouldn’t see it glisten and drop their bombs. It wasn’t re-gilded until 1998 during an £11.2 million restoration. Albert is now dressed in 23½ carat gold leaf.

Royal Albert Hall

Albert Memorial