Fleet in the City: Part 1 – The Valley of the Fleet

The River Fleet rises in Hampstead Heath meandering downhill through north London for four miles, until it exits into the River Thames at Blackfriars.

From Heath to Thames the Fleet is now culverted and runs underground, incorporated into Joseph Bazalgette’s grand nineteenth century London sewer system. Its exit into the Thames is now an inconspicuous outlet rather than a wide open inlet for what had once been a navigable Thames tributary. The word ‘Fleet’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon word for ‘tidal inlet’.

The Fleet’s story for almost four hundred years has been one of decline: river to rivulet, ditch to drain. Its reputation, for Londoners, now carries no more weight than an association with Fleet Street, a busy, commercial City highway; or with Fleet Road in Hampstead, which curls along the old route.

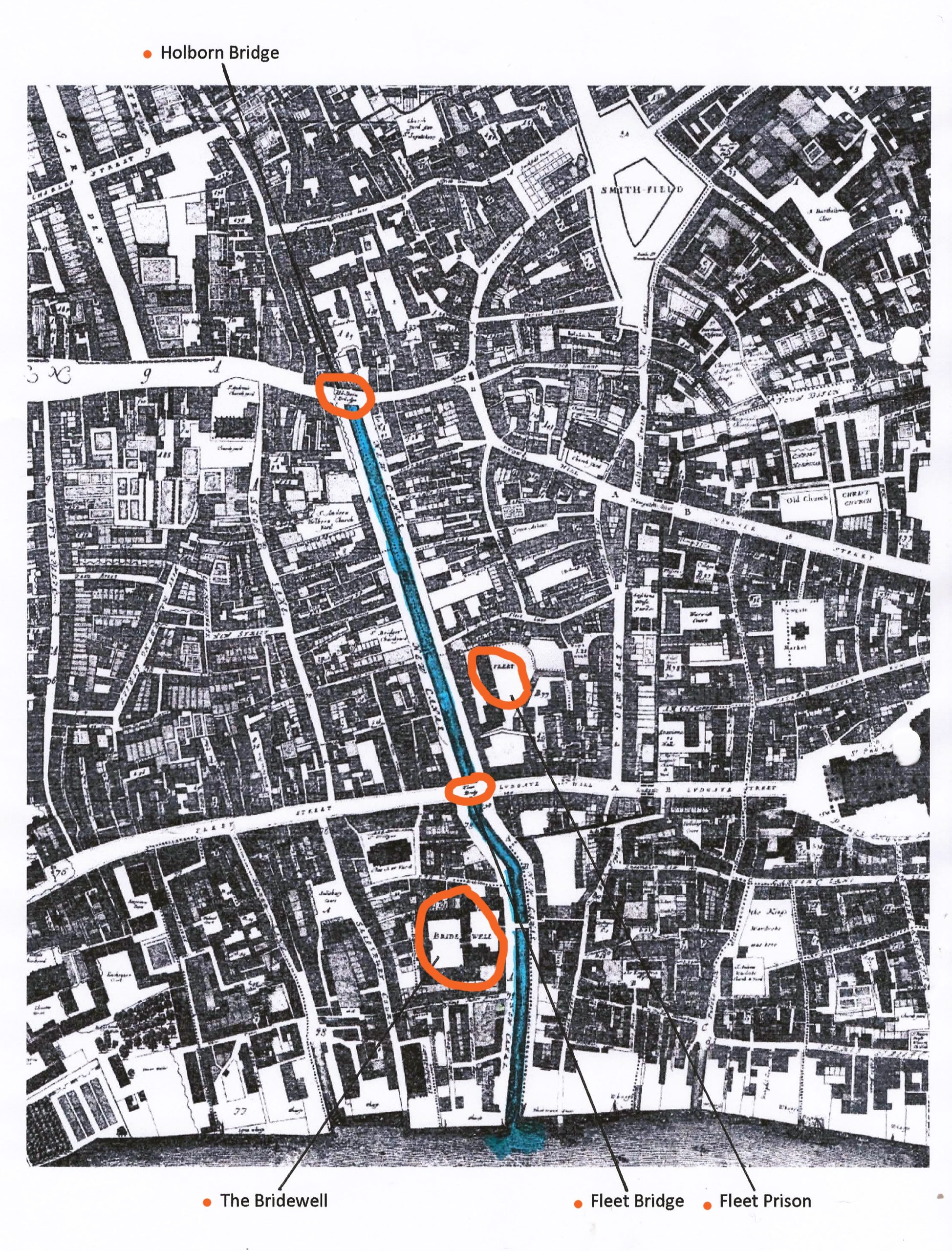

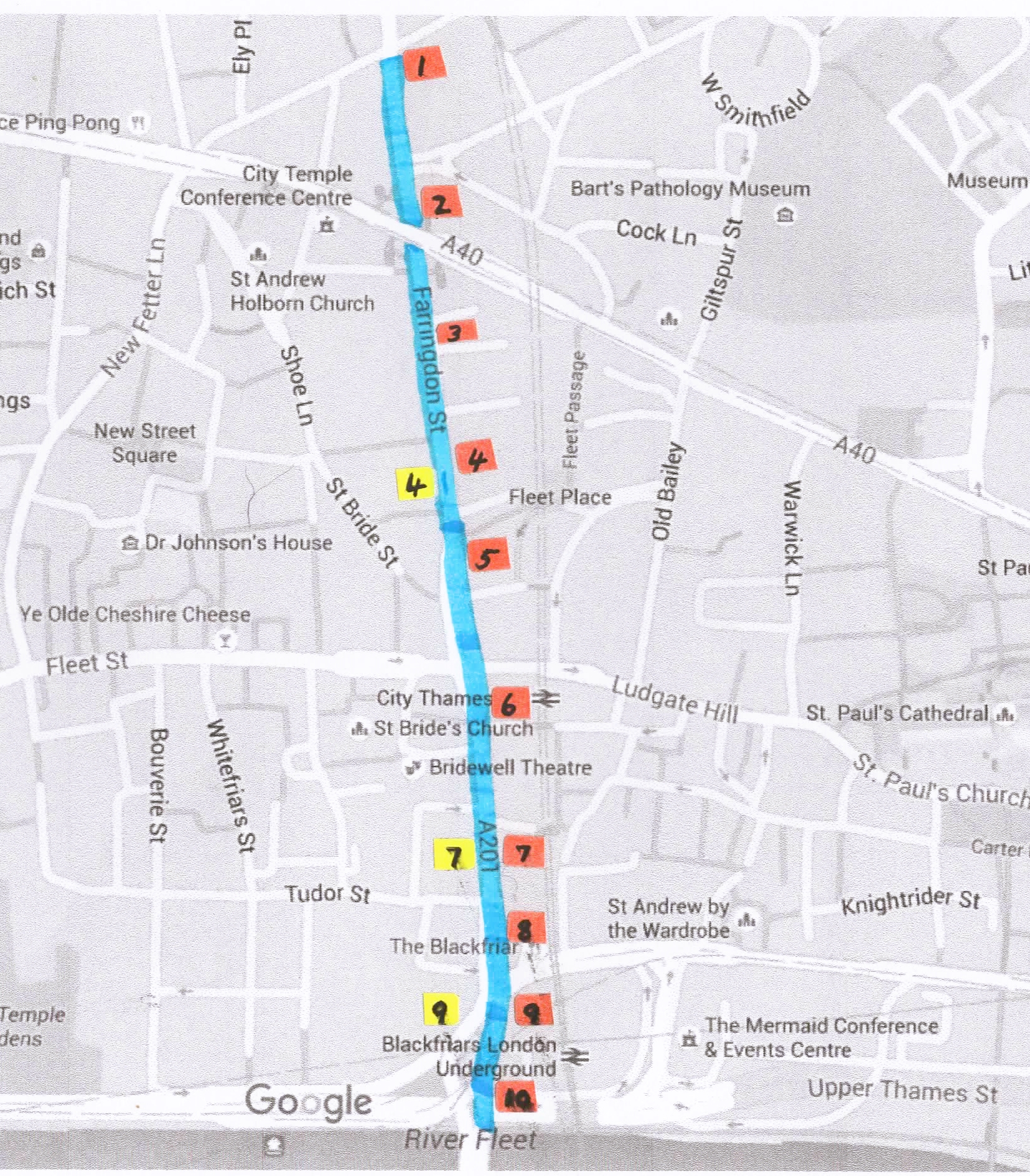

‘Fleet in the City: Part 1 – The Valley of the Fleet’ follows the rivers City of London route – formerly a navigable, bustling waterway, still recognisable as the ‘valley of the Fleet’. I’ve chosen to highlight those places which have an association with the Fleet or whose story owes itself, in some way, directly to this lost river.

Route maps are at the foot of the page.

Farringdon Street.

1) Dragon – City of London boundary marker.

The Dragon has been part of the City of London emblem since the 14th century but has only been placed on City boundaries since the 19th century.

Dragon- City of London boundary

The full Coat of Arms of the City incorporates the Shield of St George, Sword of St Paul, two dragons and the City motto ‘Domine dirige nos’ (trans. Lord Guide Us).

This silver dragon sits on the City boundary at the junction of Charterhouse Street and Farringdon Street, which was named after a 13th century goldsmith & City Alderman William de Farringdon. Running from the east into the Fleet, following the line of Charterhouse Street, had once been the Faggeswell Brook which created another City boundary until the late 1500s, when it was dammed up.

Our route takes us south, down Farringdon Street, which is essentially the route of the River Fleet. The ‘valley’ is still noticeable with slight hills rising on both sides to the east and west. From the Middle Ages the banks of the river were populated with local industries, especially butchers and tanners. These trades created a lot of waste and pollution and over time the river become noxious and then un-navigable until, in the late 17th century, Christopher Wren canalised this entire lower section of the Fleet down to the River Thames.

2) Snow Hill (east bank).

Snow Hill has nothing to do with snow. The name derives from its original name of Snore Hill which means ‘twisty hill’. Snow Hill still curves but became shortened somewhat as the street patterns in this area developed through the 19th century.

Snow Hill still twists down into the valley of the Fleet at Farringdon Street, but it once led round to Holborn Bridge which used to cross the river into Holborn Hill on the opposite bank.

This had once been part of the route carting the condemned from Newgate Prison to the Tyburn gallows, those who took ‘a ride backwards up Holborn Hill’ (obscuring the route to their final destination).

Holborn Hill and the bridge disappeared during the construction of Holborn Viaduct in the 1860s. The second part of this blog will focus on Holborn Viaduct. There is a superb tiled mural illustrating the building of the Viaduct. This can be seen in the stairwell leading up to the viaduct from Farringdon Street, on the north west side.

Farringdon Street looking south. Snow Hill on the left at the traffic lights. Holborn Viaduct ahead.

Turnagain Lane

Newcastle Close

3) Turnagain Lane and Newcastle Close (east bank).

Turnagain Lane was originally called ‘Wendagaynslane’ and it dates from the 13th century (it was Turnagain Lane by the Agas map of 1561). It too was shortened by the building of the Viaduct (see Part: 2) and the featureless rump we see today is all that remains. It originally led down to the river from Snow Hill. Now it’s cul-de-sac’d and you have to ‘turn again’ at the end. But it used to be the bank of the Fleet itself that was the dead end, where you ‘turned again’, back towards Snow Hill. Its turn has been reversed.

Newcastle Close gained its name from the sea-coal that was unloaded here from the Middle Ages. Coal from the North East would sail from Newcastle around England’s east coast, turn into the Thames estuary, sail upriver and then into the navigable River Fleet. Here the ships would unload their cargo. Sea-coal was the name given to coal from the North East of England, both washed up on the beaches and later mined inland, possibly because it arrived in London having been sea-borne.

Bear Alley close by possibly takes its name from a former Bear Tavern on or near the site.

4) Hoop & Grapes Public House and Harp Alley (west bank).

The building we see dates from 1721 and it’s the only building to survive on this stretch from when the Fleet was open water. The cellar contains the remains of a late 17th century quayside warehouse, hinting at the original purpose of this old working building.

It became a pub in 1830. There is some Second World War bomb damage to the front. Ironically the Hoop & Grapes sits on the corner of Harp Alley named after the long gone 17th century Harp Tavern.

This building is the only one that really helps us create an image of the Fleet as an embanked river with wharves and working buildings lining the banks of this industrious river.

Hoop & Grapes pub – surrounded by construction.

Harp Alley

5 Fleet Place – former Congregational Hall

5) 5 Fleet Place (east bank).

5 Fleet Place is an office block which stands on the site of the former:

- Fleet Prison (1170 – 1844). The City of London housed many prisons. This is one of the more infamous which, like Newgate Prison, had many incarnations. The original building was destroyed during the Peasants Revolt of 1381. The first rebuild then burned during the Great Fire of London in September 1666. The Gordon Riots of June 1780 did for the next one. The Fleet Prison was a general gaol for debtors and others which by the 1800s could hold 300 prisoners, and their families.

But it’s for its ‘Fleet Marriages’ that the prison gained notoriety and provided a byname for ‘slippery-but-legal’ marriages. From about 1613 these marriages were conducted by clergymen imprisoned for debt. They were legal, quick, cheap and away from the betrothed’s home parish – huge numbers of people were migrating to London from all corners of the country. The ceremony provided a legal loophole without the need for a bann or licence (the Prison was outside the jurisdiction of the church) and up to thirty weddings per day were being performed by the early 18th century, that’s over 10% of all marriages in England. The Marriage Act 1753 closed the loophole.

- Congregational Memorial Hall (1875 – 1968) was built on what had been part of Ludgate Station (and formerly the Fleet Prison). The Labour Party was formed here, under the name of the Labour Representation Committee, in February 1900. Future Prime Minister Ramsey McDonald was its first President. It became the General Strike HQ in 1926 and the British Union of Fascists held their first rally here in 1932.

Old Fleet Lane, which is north of 5 Fleet Place, was once much longer and connected to Old Bailey.

Old Seacoal Lane (east bank).

Old Seacoal Lane

Old Seacoal Lane, like Newcastle Close, was a docking point on the Fleet for sea-coal shipped from the North East. Sea-coal was cheap and very smelly. The 17th century London chronicler John Evelyn wrote that Londoners “breathe nothing but an impure and thick mist, accompanied with a fuliginous and filthy vapour”.

Stonecutter Street and St Bride Street (west bank).

Stonecutter Street led down to Wren’s canalised Fleet and was known as Stone Cutters Streete. Just to its south was St Bridget’s Churchyard and both are featured on the Ogilby and Morgan map of 1676. The churchyard may have been an overspill burial ground for the main St Bridget’s Church (St Bride’s) on Fleet Street. St Bride Street, not yet constructed, clearly takes its name from this association.

6) Ludgate Circus.

The Ludgate was the westernmost gate through the City wall (demolished 1760). It also provides an enduring myth for the source of London’s name. This made-up version of London’s origins – mainly constructed by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century – begins with a city built by the mythical Brutus of Troy (which approximates to the 12th century BC) later rebuilt by the mythical pre-Roman King Lud who named his city Caerlud (city of Lud) which then evolved into Caerlondein. It’s more than likely that ‘ludgate’ derives from ‘floodgate’.

Ludgate Circus replaced the Fleet Bridge, which used to cross the river and later the canal. This had been the main bridge connecting the City to Fleet Street and onwards to Westminster. The upper canal from Ludgate to Holborn had been enclosed from 1737 when the Fleet Market covered its entirety. The lower part, leading down to the Thames, was covered in the 1760s when it became New Bridge Street and the approach to Blackfriars Bridge.

Ludgate Circus towards Fleet Street

Fleet Street (west bank).

Fleet Street is simply named after the river and dates to the early 11th century. In the Middle Ages, before it became a byword for ‘the press’, it was lined by many fine London houses for provincial Bishops and Abbots.

Printers had become established in Fleet Street by the early 1500s. The first, Winkyn de Worde printed 800 books. His office was on the south side opposite Shoe Lane under the sign of the sun. Richard Pynson was a legal publisher who printed the Canterbury Tales and 371 other books. He was also printer to King Henry VIII and could be found under sign of the George. Every shop had a hanging sign as their identity, some quite large. In 1718 one sign fell down and killed four people.

The first Fleet Street newspaper ‘The Daily Courant’ started printing in 1702, its offices next to the bridge. It wasn’t only newspapers and printing that made the area famous.

There are tales of an early 18th century gang of young aristocrats called ‘the Mohocks’ who based themselves near here and were infamous for rolling people down Snow Hill in a barrel. They also sexually assaulted their female victims and cut off the noses and hands of their male victims, so it’s said. There isn’t strong proof to substantiate any of these reports. Could this have been an early example of how the new Fleet Street press discovered that sensation sells newspapers? For the rest of the 18th century the name ‘Mohawks’ became attached to any rowdy gang of drunken young men.

New Bridge Street (1764) – the approach to Blackfriars Bridge.

Pilgrim Street (east bank).

Pilgrims and worshippers visiting St Paul’s Cathedral could sail up the Fleet and disembark here.

7) 14 New Bridge Street (west bank).

On the west bank of the Fleet, between Ludgate Circus and the Thames stood Bridewell Palace, built in 1515 by Henry VIII. The holy well, or spring, was originally nearby at St Bride’s Church.

In 1529 Katherine of Aragon’s last meal as Queen was here and in 1533 Holbein the Younger probably painted his masterpiece ‘The Ambassadors’ here. But this was clearly one palace too many for the son of King Henry and in 1553 Edward VI gave the Palace to the City of London. From this date until 1855 it served as a prison, the original ‘Bridewell’ which became as much a generic name for prisons as another famous London gaol called ‘the Clink’.

Public floggings took place twice weekly, ending only when the President of the Court banged on the table with a hammer. Although in 1700 the ‘enlightenment’ shone in when it became the first prison to appoint a doctor and prisoners were allowed straw beds.

Large parts of the original palace and then prison had been destroyed in 1666 during Great Fire and rebuilt. In 1802 a new gatehouse was constructed and this survives as 14 New Bridge Street. A small stone bust of Edward VI sits in the keystone above the entrance.

Pilgrim Street – vista to St Paul’s Cathedral

14 New Bridge Street

New Bridge Street – looking south to Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Pub

8) Blackfriars Public House (east bank).

The Blackfriars pub dates from the 1870s and was remodelled during the early 20th century. Its design is ‘arts & crafts meets mock art nouveau’. Vaulted, mirrored, gilded, enamelled and mosaiced inside and with a sculpture of a laughing friar above the entrance, it ‘dizzies the drinker’.

The pub is named after the nearby site of the former Blackfriars Monastery, a Dominican priory dating from the late 13th century and dissolved in 1538. In 1528 a Papal Court sat in the Priory to hear Henry VIIIs petition for divorce from Katherine of Aragon. The Court ended by refusing the petition and in his response Henry began the English Reformation. The only surviving part of the monastery is a fragment of wall in Ireland Yard – close to where William Shakespeare is known to have lived in 1613.

9) Watergate and Unilever House (west bank).

Watergate is named after the now long-gone watergate from the Thames into Bridewell Palace.

Unilever House is the Unilever Headquarters. Constructed in 1932 and the largest inter-war build in the City of London its style is described as Neoclassical Art Deco. Lord Leverhulme commissioned the design before Lever Brothers merged with Dutch Unie to become Unilever in 1930.

The curved ground floor is quite austere with no windows, to block out street noise. The giant ionic columns between the fourth and sixth floors create a dominating landmark building visible from all angles. The two corner entrances have large sculptures above the doors called ‘Controlled Energy: man and horse’ and ‘Controlled Energy: woman and horse’.

Unilever has annual sales of over £50 billion and its brands include: Vaseline, Surf, CiF, Hellman’s, Flora, Comfort, Dove, Lynx, Persil, Bovril, Knorr, Marmite and Pot Noodle.

Unilever House

Watergate

10) Blackfriars Station (east bank) and Blackfriars Bridge.

Blackfriars Station was constructed in 1886 for the London, Chatham & Dover Railway (LC&DR). From 1864 the trains terminated closer to Ludgate Hill but this temporary station was replaced by St Paul’s Station on the present site. The new station and new rail bridge over the Thames were designed by Joseph Cubitt, who had also designed the rebuilt Blackfriars Bridge. The original Blackfriars Underground Station had opened nearby in 1870.

Both stations have been connected since 1886 although the full name change from St Paul’s to Blackfriars didn’t occur until 1937, following the Central Line’s confusing renaming of Post Office Underground Station to St Paul’s Underground Station . The piers of the original 1864 rail bridge over the Thames can still be seen next to its still functional 1886 replacement.

A complete rebuild was undertaken in 2012 with new platforms on the remodelled rail bridge and a brand new entrance providing access from the south bank. The station has 14 million users annually.

Blackfriars Station

LC&DR destinations

There have been two Blackfriars Bridges. The first was constructed in 1769 and was only the third bridge to span the Thames in London (after London Bridge and Westminster Bridge). It was officially called the William Pitt Bridge. In June 1780 the Gordon Rioters destroyed the Toll House and stole some toll money (presumably after they had burned down the Fleet Prison).

In 1869 Joseph Cubitt’s new bridge was opened by Queen Victoria on the same day she officially opened Holborn Viaduct. Queen Victoria’s statue stands at the bridge head on the north side.

Italian banker Roberto Calvi (known as ‘God’s Banker’) was found hanged under the bridge in June 1982. Five bricks and $14000 were found in his pockets. He’d been accused of embezzling Banco Ambrosiano and fled to London. This was not suicide but murder; and still a mystery. Calvi was a member of an illegal Italian masonic lodge Propaganda Due (P2), who referred to themselves as ‘frati neri’ or ‘black friars’. This led some to think that Calvi was murdered as a warning and that the symbolism associated with the word Blackfriars was no coincidence.

This is also where the Fleet joins the Thames. The outlet discharging the waters of the culverted River Fleet can be seen at low tide.

Interestingly Blackfriars Bridge is part of the City of London – as are all of the bridges that span the Thames into the City. If you walk down to the south end of the bridge you’ll find the silver dragon, marking the boundary of the City of London.

Ogilby and Morgan Map 1676

Fleet in the City