The British Museum: Top 12 Highlights

The British Museum’s origin has no connection to royalty or church. It has always been a museum for people, dedicated to people: displaying their arts, exhibiting their cultural objects and explaining their civilisations. It’s one of the great world museums, visited by millions of people every year.

Admission is free: 10.00am – 6.00pm.

Here is the London Explorer’s Top 12 Highlights of the British Museum.

- The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1.

The museum has a permanent collection of some eight million works, pretty much the largest and most comprehensive in the world, and over 80,000 objects are on display at any one time. The collection is drawn from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from two million years ago to the present day. Not surprisingly the British Museum is a vast building.

British Museum

Established in 1753 and originally based on the collections of the physician Sir Hans Sloane the museum first opened to the public in Montagu House, on the site of the present building. Its growth since then has largely been the result of expanding British colonization and the subsequent acquisition, gifting and purchase of millions of items.

The museum’s grand Palladian façade on Great Russell Street was designed by Sir Robert Smirke in the early 19th century. Its forty four Ionic columns, each 45 feet high, are based on those of the temple of Athena Polias at Priene in Turkey. The enormous pediment over the main entrance is decorated with sculptures by Sir Richard Westmacott depicting – according to the British prejudices of the time – The Progress of Civilisation.

The Great Court, British Museum

Once inside you’ll begin your visit in the Great Court, a spectacular modern space suitably monumental for such a great museum. This was once an open courtyard but since its redesign in 2000 you can wander beneath a geometric glass roof, creating the largest covered square in Europe.

Within the Great Court is a superb 360° book and gift shop (if you’re a book-buying addict DON’T go inside), some classy coffee shops, bathrooms and the information desks. The dominating central feature of the Great Court is the original circular Reading Room designed by Samuel Smirke, brother of Robert, which now houses temporary exhibitions.

This huge and impressive building is a highlight itself, especially Smirke’s front and the Great Court.

- The Enlightenment Gallery. Room G1.

Rosetta Stone replica, British Museum

Step back in time into one of the oldest rooms in the museum and the only gallery which looks like it did for the original 19th century visitors. The Enlightenment was an age of reason, experimentation and learning that spread across Europe and America from about 1680 to 1820.

This 300-foot-long gallery housing thousands of diverse objects illustrates how British people understood the world at this time. Enlightened men and women believed that observing both the natural and manmade world would unlock ancient mysteries and expand their understanding. Their passion for collecting objects, from fossils and flints to Greek vases and ancient scripts, was matched only by an impulse to create order, to catalogue and to classify. Their formation laid down the rules of how we see museums the way we do today.

There is a replica of the Rosetta Stone in this gallery, which you can touch and take photos next to, and before you visit the other galleries see if you can find the Japanese merman.

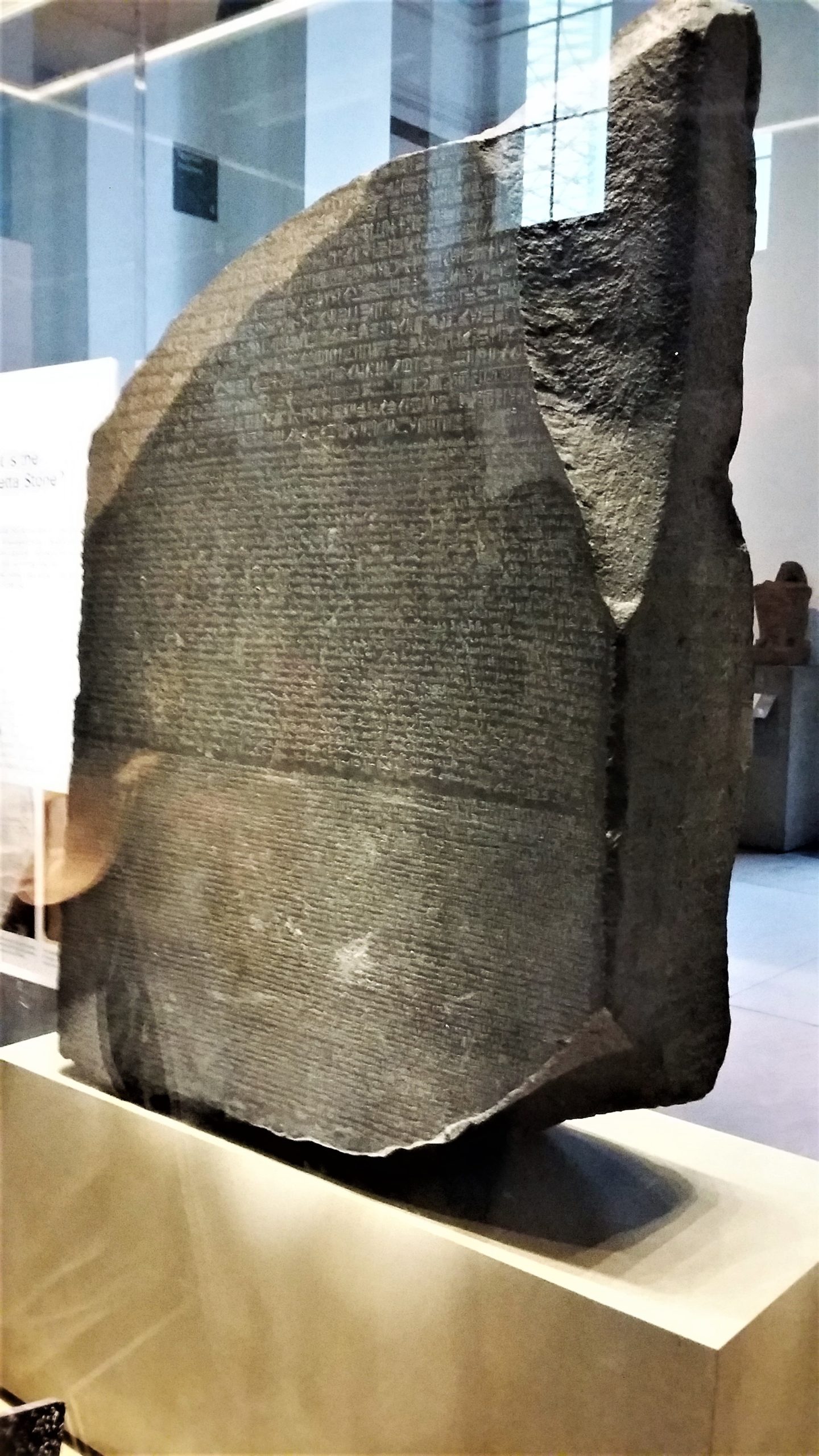

- The Rosetta Stone. Room G4.

Rosetta Stone, British Museum

Probably…possibly…the most famous exhibit in the museum. The Rosetta Stone is a stele, or monument, inscribed with three versions of a proclamation issued in Egypt in 196 BCE praising King Ptolemy V. The Ptolemy’s were of Greek decent and this decree announcing an endowment to an Egyptian temple was a politically important event and a clever way to keep the Egyptian people happy. The stone ended up as building material, part of a wall post in a post-Roman era building, and was discovered as such in 1799.

What is it that makes the Rosetta Stone so important?

The top and middle texts are in ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic script and demotic (later Egyptian) cursive script. The bottom section is in ancient Greek. As the decree has only minor differences between the three versions the Rosetta Stone proved to be the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs – many learned men could read and write ancient Greek. Lots of copies were dispersed by Ptolemy V through Egypt, but this was the first discovered and therefore the ‘Rosetta Stone’, the source, for all future translations.

- False door and architrave of Ptahshepses. Room G4.

We’re sticking with Egyptian hieroglyphs; but this time on a large, incredibly well-preserved tomb entrance which predates the Rosetta Stone by over 2000 years. Ptahshepses was a high ranking official of the Fifth Dynasty pharaoh Nyuserre. He would have been considered one of the elite members of the royal court. Ptahshepses’s tomb, or mastaba, is considered to be one of the most unique non-royal tombs of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (2686 – 2180 BCE) to survive.

False door of Ptahshepses

A mastaba (‘eternal house’) is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure made out of mudbricks. They were typical burial sites for eminent people during Egypt’s Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. It was during the Old Kingdom that kings began to be buried in pyramids instead of in mastabas.

The false door at the mastaba’s front served as a link between the living and the dead. Food and drink offerings would be placed here – essential even in the afterlife – and it was believed that the spiritual double of the deceased would emerge to eat and drink.

Why is this item one of my highlights?

Its preservation is superb (it’s almost 4500 years old). From top to bottom the carving of the hieroglyphs is sharp, detailed and – because of the Rosetta Stone – understandable. Even residues of original paintwork survive. It has allowed Ptahshepses to travel through time and be remembered by us. For more connections to rituals for the dead of ancient Egypt also see highlight no.10.

- Winged Bulls and Lions from Nimrud and Khorsabad. Rooms G4, 6, 7, 10.

Lamassu, British Museum

Lama was an ancient Assyrian goddess whose depiction evolved into the large stone carvings of winged lions and bulls, with human heads, we see exhibited today. We call them Lamassu. They are generally protective gateway figures displayed in pairs, usually made of gypsum (marble) and carved from one piece of stone. The lines you may observe horizontally and vertically, literally cutting through the marble, were made to enable easier transportation across land and sea to Britain.

The Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria (modern northern Iraq) existed from approximately the 26th – 7th century BCE. These large marble sculptures were a striking feature of their palaces and temples. Sizes could reach 15’ square and weigh over 16 tons each and most were painted.

Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headwear of a divinity and braided hair and beards typical of royalty. The body is either a bull or a lion, the form of the feet being the main difference. Lamassu tend to be ‘double-aspect’ figures; viewed from the corners they have five legs. From the front they appear to stand, and from the side they walk.

- Assyrian Lion Hunt reliefs from Nineveh. Room G10a.

It’s easy to see why the royal Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal is a highlight. The alabaster reliefs depict an Assyrian king at the height of his powers, his divine right established, his empire unchallenged. Is it any surprise that the Victorians loved these carvings, comparing Great Britain’s imperial powers to those of a mighty biblical ruler (it’s thought Ashurbanipal could be Osnappar in the Book of Ezra).

Assyrian Lion Hunt, British Museum

The Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal comes from the North Palace of Nineveh and is regarded as a masterpiece of Assyrian art. The panels depict a formalized, ritualized hunt by King Ashurbanipal (668 – 627 BCE). The hunt was staged in an arena where captured Asian lions were released from cages for the king to kill from his chariot with arrows, spears or by sword. They were made around 645 – 635 BCE and like the Lamassu they would have been painted.

The hunt progresses through the panels, from the preparation of horses, grooms leading them into the arena, securing horses to the chariots, spectators gathering on the overlooking hills, caged lions before release and then the king’s hunt itself.

People are mostly seen in formal side-on poses, including the king in his several appearances. The lions are carved in a variety of naturalistic poses, alive, dying and dead. Their nobility is artistically represented but they are ultimately vanquished by the one foe more powerful than them.

The reliefs were probably carved flat and it’s still not known how this level of detail was achieved; no steel existed for fine carving. Perhaps Ashurbanipal himself oversaw production as we can see where mistakes have been corrected, more regarding accuracy rather than craftsmanship.

- Parthenon Marbles (Elgin Marbles). Rooms G17, 18.

Parthenon Marbles, British Museum

If you’re reading this in 2050 these world-famous pieces may no longer be in the British Museum. They are quite possibly the most contentious museum exhibits in the world with the Greek government in almost continuous campaign mode to have them returned to Athens.

The Parthenon Marbles are also known as the Elgin Marbles after Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin who brought the collection to England in the early 1800s. The marbles are a collection of Classical Greek sculptures made under the supervision of the master sculptor Phidias. They were originally part of the temple complex of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens.

Acropolis means High City. The Athena Parthenos (Maiden) was the room for unmarried women and was originally only part of the entire temple. The Parthenon temple celebrates the Athenian (and their Greek allies) victory over the Persians at the sea battle of Salamis (480 BCE). The Persians had all but destroyed Athens previously and the wealth of Athenians and their perceived cultural superiority was reflected in rebuilt Athens and the Parthenon (447 – 432 BCE).

In 1801 the Ottoman’s controlled Greece and this enabled the Earl of Elgin to get official permission to remove the marbles and ship them to England. They had arguably been subject to some neglect over the centuries. In Britain the acquisition of the collection was contentious even then, supported by some but not by others. Lord Byron likened Elgin’s actions to looting.

Following a public debate in Parliament and the subsequent exoneration of Elgin, he sold the Marbles to the British government in 1816 for £35,000 – less than half his total costs.

- Mayan bloodletting lintel from Yaxchilan (Lintel 24). Room G27.

Mayan Bloodletting Lintel 24, British Museum

The plainly named Lintel 24 tells quite an elaborate story. It’s an ancient Mayan carved limestone panel from Yaxchilan (the Place of the Split Sky) in Mexico. The images and hieroglyphs within the lintel illustrate and describe a bloodletting ritual that took place in 709 CE, or 5 Eb 15 Mac in the Mayan calendar. The lintel itself was carved around fifteen years later. It’s not often we see something this gory represented in an object.

The lintel shows the Mayan ruler, Shield Jaguar, hold a torch and watch as his consort Lady Xoc (Shoke) pulls a rope studded with obsidian shards through her tongue in order to summon a Vision Serpent. Lady Xoc was Shield Jaguars aunt, his mother’s sister. They had no children.

Mayan religion believed that serpents were the medium by which celestial bodies, like the sun, moon and stars, crossed the sky. The shedding of a snake’s skin also made them a symbol of rebirth and renewal. The Vision Serpent is thought to be the most important of the Mayan ritual serpents.

During a bloodletting ritual participants experienced a vision in which they communicated with the ancestors or gods. Visions took the form of a giant serpent which served as a gateway to the spirit world. The god summoned would emerge from the serpent’s mouth and participate in the ceremony. Conjuring the gods was crucial to the success of their reign.

So how did participants see a Vision Serpent? It’s thought that massive blood loss caused by the obsidian shards made the brain release a large quantity of natural endorphins. These are chemically related to opiates and as the body went into shock hallucinations and visions occurred.

Fortunately, perhaps, we know every grisly detail of this ritual. Some of the turquoise paint survives on parts of the panel too.

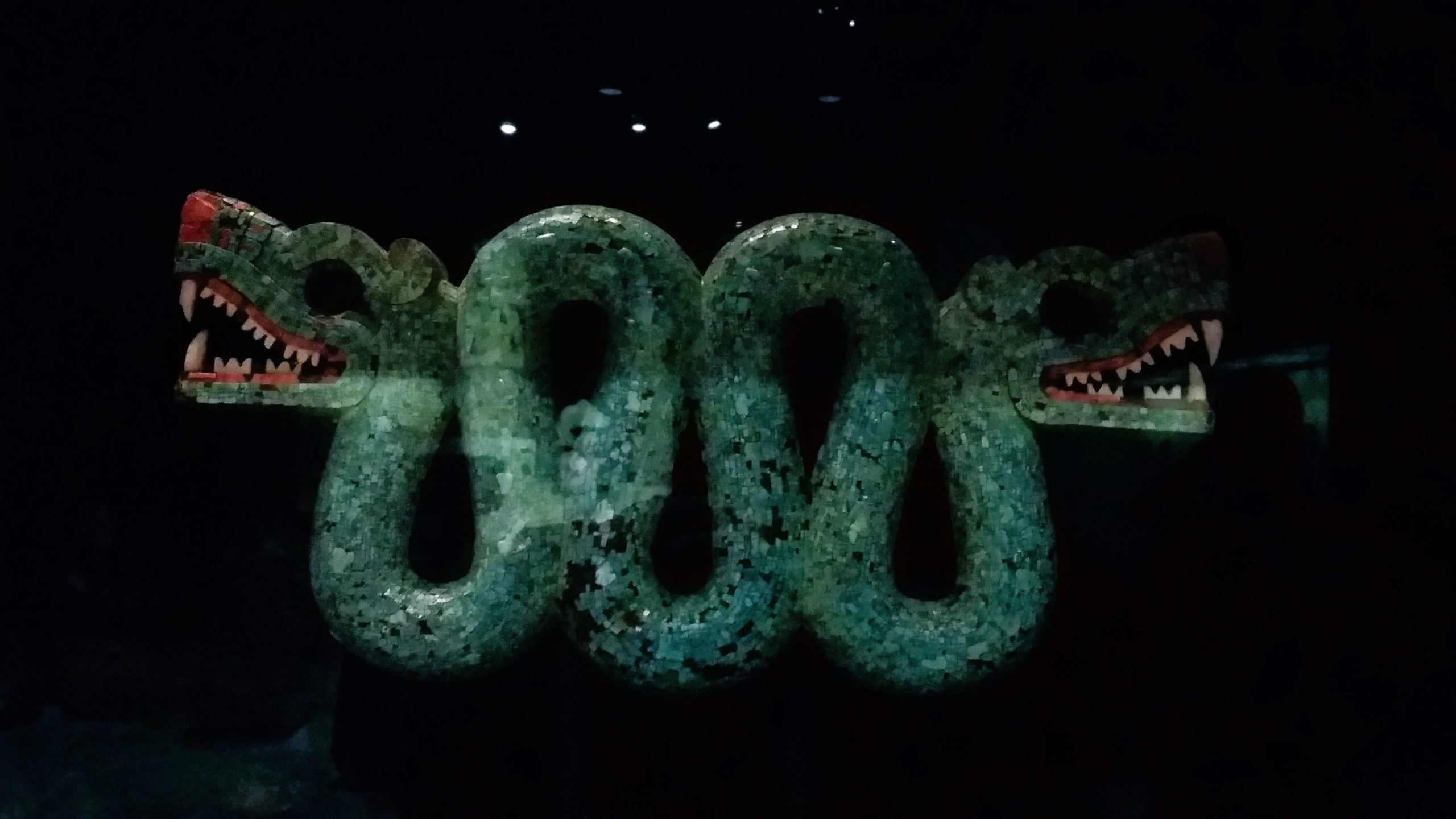

- Aztec double-headed turquoise serpent. Room G27.

There is a connection of sorts between this exhibit and highlight no.8. The serpent features heavily again, as does the colour turquoise. The double-headed serpent is an Aztec sculpture composed of turquoise pieces, spiny oyster shell and conch shell on a wooden base. It might have been worn or displayed in religious ceremonies and it’s possible that this object may have been one of the gifts given by the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma II, to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés when he invaded in 1519. An Aztec prophecy foretold that God would be white skinned and bearded.

Aztec serpent, British Museum

In fact, the gifts horrified Cortés. Aztec art seemed to focus purely on death. Within two years the Mexican Aztec empire was destroyed and 90% of its people had died from disease, war or enslavement.

This item shows an undulating serpent with a head on each side. The outer body is covered in a mosaic of turquoise with red spiny oyster details, all glued to the wooden body with pine resin. The back had once been covered in gold leaf (residue survives). The back has also been hollowed out, possibly to make the sculpture lighter to wear in ceremonies.

The Mayans and Aztecs both used serpents in their art and rituals. The serpent or snake represents fertility and rebirth (the shedding of skin, one body two heads). Two heads could also represent earth and the underworld (teeth symbolise death). There are over 700 species of snake in Mexico and the Aztecs used them in all sorts of decorations. Turquoise symbolised life-giving water. It’s also the colour of maize, a staple crop.

- Egyptian Galleries. Rooms 3.62/63/64.

The British Museum contains the largest collection of ancient Egyptian objects outside Egypt. The Egyptian Galleries mainly explore how ancient Egyptians confronted and dealt with death and the afterlife, something which held special importance and meaning for them.

Mummification and magic, ritual and burial are all investigated through the objects and tomb artefacts on display. These include mummies, coffins, funerary masks, portraits, pottery, animals, papyri and many other objects designed to be part of the process, often buried with the dead.

There are several mummies on display in these galleries with explanations demonstrating how the use of modern technology can investigate mummies without unwrapping them.

Egyptian Mummy, British Museum

- The Battersea Shield. Room 3.52

There’s not much on display in the museum which can be directly associated with London. So, I love the fact that this 3rd – 1st century BCE shield was found on the banks of the River Thames in London.

Battersea Shield, British Museum

It’s made of bronze with red enamel and was discovered in 1857 on the south bank of the Thames in Battersea. When this shield was made neither London nor Battersea existed. There were settlements near to the river though and it’s thought local iron age Britons may have placed this well-crafted, highly valued shield in the river, perhaps as an offering.

The artistic style is early Celtic, represented by the flowing patterns of swirls and scrolls. Influences of Greek and Italian styles are there too, which shows that Britain was not an isolated island of savages but connected to the continent of Europe by trade, art and culture. Unique ‘British’ styling is apparent as well, seen especially through the owl-like faces in the metalwork.

- Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. Room 3.41.

The final highlight is something special and specifically English, from East Anglia; perhaps the greatest find to emerge from the people who would come to be known as the Anglo-Saxons.

Sutton Hoo helmet, British Museum

Sutton Hoo in Suffolk is the site of an early 7th century burial ground which contained an undisturbed ship-burial for a king. In post-Roman Britain of the 6th – 10th centuries kingdoms were small; they were not nations but regions of varying sizes ruled over by warlords.

The ship-burial probably dates from the 620s and was excavated in 1939. It is one of the most significant archaeological finds in England for its size and completeness, far-reaching connections and the quality and beauty of its contents. The site included a wealth of Anglo-Saxon objects of outstanding historical and archaeological importance.

The burial is almost certainly that of Raedwald, a king of the East Anglians. Although he converted to Christianity he continued to worship the Norse gods as well. East Anglian kings claimed decent from Julius Cesar and Wodin, the best of the Romans and the Norse. Many of the objects have a style that is now recognised as uniquely English. Although materials came from as far away as India the designs used to make the objects show that a specific ‘insular’ English style had developed.

The most significant objects from the ship-burial are those found in the burial chamber, including a ceremonial helmet, a suite of metalwork dress fittings in gold and gems, a shield and sword, various weaponry, a lyre, shoes and buckles, pots and jars, coins and pieces jewellery and silver plate from Byzantium. As for the remains of Raedwald, they had dissolved in the acidic soil by the time of discovery.